Not only have we survived the two years of the pandemic, we have grown, our voices are increasingly merging like rivers and becoming freer. Although we sing at a distance (perhaps, because of this), we learned to hear each other better and better, we hear the source,“the source“, that is written about

in the book "The Philosophy of Singing" by Bettina Hesse (our choir singer)

Thanks to my favorite choir! We're moving on!

Thank you, dear Christian Herrmann for the photos. Thank you, #LutherKirche and #SüdstadtLeben for the open doors!

This journey began about 30 years ago, in a conversation with Professor Yaroslav Hrytsak,( with whom we met in line for a Polish visa,) I heard for the first time about Hasidic culture in Ukraine. (Mr. Yaroslav, by the way, also lent me a dictaphone for my first expedition trip in search of forgotten Ukrainian songs.)

The project "Our Singing for Babyn Yar" started for me with stories by Svetlana Kundish about the symbolism and significance of Nigun, about how singing together helps us to "lift our hearts“, overcome pain, „descent into darkness, for to be able to rise up."

Thank you, Yuriy, for ending the play with your statement that you feel yourself in Ukraine today better, than in the time, when we shared the fate of minorities in the USSR.

I will repeat again and again - the thoughts, questions, the hope voiced by me in the play - would not be possible without YOU! it is thanks to all of you, dear and dearest! To all who do not stop, are not afraid, do not agree. I bow my head to you and thank you for being in Kyiv at „the birth“ of the play.

It is symbolic for me that I started this year with the play "I want to live", around the poetry and fate of the young Selma Meerbaum, our "Anna Frank from Chernivtsi" (collaboration with Theater Lesi, Theater Neue Buhne and Futur 3). And I end this year with the play „Songs for Babyn Yar“.(Thank you dear people from Dash Arts!!!!)

I would like to emphasize with great pride and gratitude that this work was possible thanks to the support at all levels, thanks to trust and fight for it of the Ukrainian Institute and the Goethe Institute! The word "thank you" will not fit everything I feel! But THANK YOU!

A friend of mine from Warsaw, who could only see the show online, said how good it is to know that „the light is also active and flows into such projects!“ I also truly believe that it is our responsibility to be able to share OUR SINGING FOR BABY YAR over and over again. I believe it will happen!

The photo taken by dear Josephine Burton on December 7 in Babyn Yar reminded me of another trip, more than 20 years ago, with Victoria Hanna to Medzhibozh, Sataniv, Mykhailivtsi and Uman.

It is blessing to share this road with you!

I am almost a bit embarrassed - I am again so lucky to be part of such amazing project!

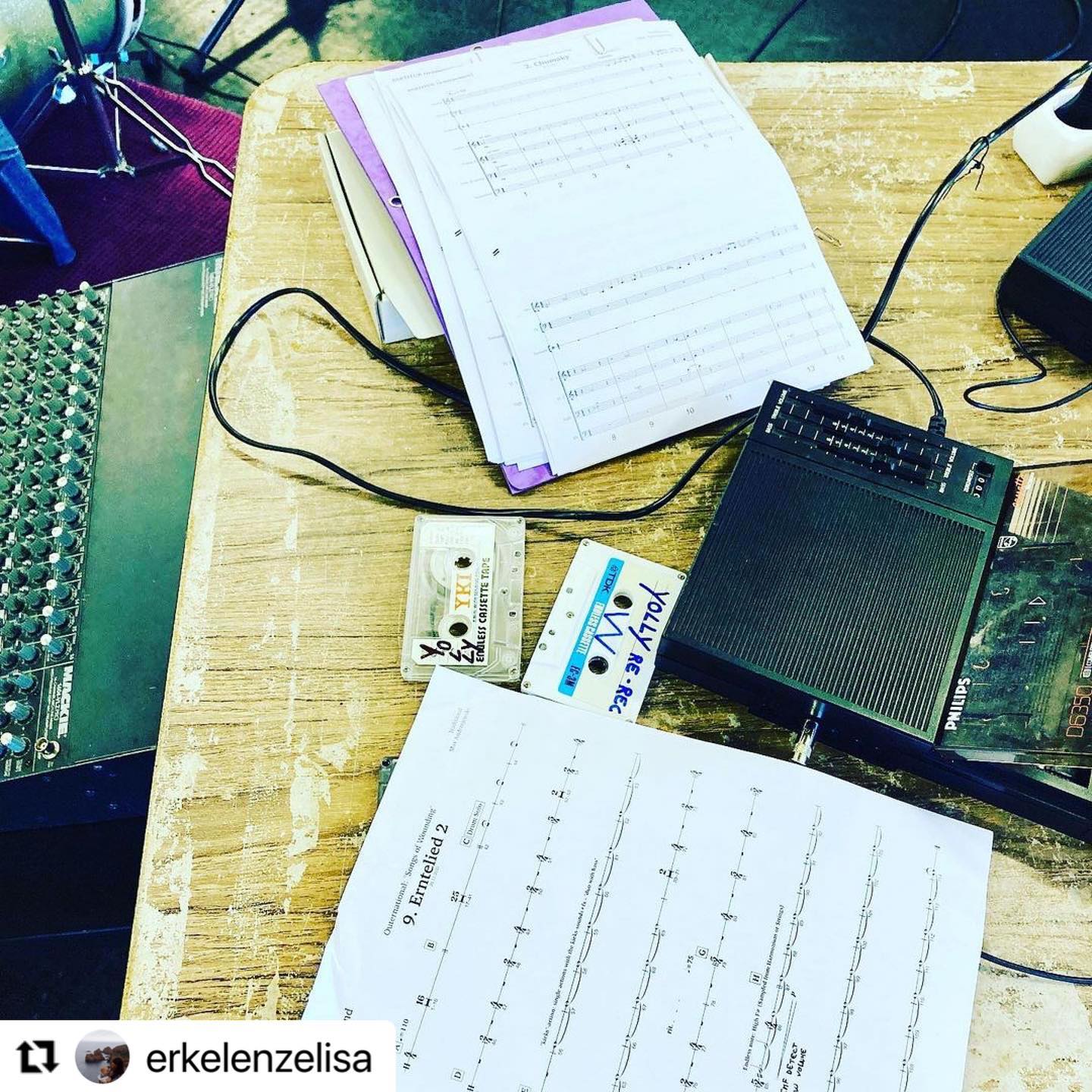

Yesterday we started rehearsals of Songs of Wounding curated by Elisa Erkelenz - Compositions of Max Andrzejewski around Ukrainian traditional songs. For a unique ensemble - barock string quartet, drums, double bass and electronics. Here is a real meeting of old and new music. Fantastic musicians!

Premiere on Thursday, December 2 in Berlin radialsystem Outernational: Songs of Wounding

And I already dream of further development in Ukraine . I dream about meeting of Max and Золтан Алмаші, James Banner and Mark Tokar, Marta Zapparoli and Alla Zagaykevych.

And between dreams - I rehears, because all the songs I chose for this work are for me also new. I never sung them before.

Who is in Berlin? Welcome

"Despite the horror, the tone is never angry, mainly elegiac and questioning, asking how do we sing about such events, or make art out of it? Important questions in this context, powerfully realised." Simon Broughton

https://www.songlines.co.uk/live-reviews/live-reviews/songs-for-babyn-yar